Going, Going, Not Yet Gone: The Quest to Save Thailand's Endangered Apes

It's not everyday that you accidentally adopt an ape.

The ape in question is Emily, a 13-year old gibbon, and the you in question is me. And here begins our story.

Located in Phuket, Thailand, I’ve found myself at the Gibbon Rehabilitation Project, a local initiative with a big mission: to return Thailand’s most intelligent wildlife species, the gibbon, back to the wild, where it was previously poached to extinction.

Located in Khao Phra Thaeo National Park, the Gibbon Rehabilitation Project is just 20 kilometers outside Phuket city. One of Thailand's most visited destinations, Phuket is more known for its beaches, resorts, and nightlife than for its rainforest, which used to cover much of the island. In fact, this national park is the last remaining evergreen rainforest on the entire island, with an area of about 23 km² out of the island's total 543 km².

While situated within the national park, the Gibbon Rehabilitation Project is a completely independent project, an NGO dedicated to gibbon conservation and community and visitor education. Today, Jeremy and I, along with our friend Claire, have ventured out to the project site to learn more about the plight of the gibbon and what this project is doing to save them. Arriving at the front gate, we’re greeted by our guide for the day, Roch, who has worked at the project for over 16 years. Wearing an outfit only befitting a gibbon rescuer, he’s decked out in tall rubber boots, dark pants, a fanny pack, and a pink shirt emblazoned with an illustrated gibbon.

Gibbons are arboreal apes that live in the wild in the tropical and subtropical rainforests of Southeast Asia. With their round faces, fluffy coats, and smaller stature, they’re not only very cute, but also quite the vocalists: they communicate with each other by "singing" across large distances. To my ears, their call sounded like something between whooping and a siren — listen below to hear for yourself:

The call is often used to attract or communicate with a mate — a serenade that inspires lifelong partnership. Known to be monogamous, gibbons pair up for life and raise their offspring together, staying as a family unit until the children grow up, move out, and leave their parents empty-nesters.

Unfortunately, though, many gibbons don’t make it that far into life in the wild — globally, gibbons are one of the most threatened primates. In Thailand and across many countries in Southeast Asia, a wicked combination of the tourism industry, the illegal pet trade, and habitat loss are driving gibbons to the brink of extinction. Though the impacts of these factors are inseparable, I think it's important to explain each distinctly given how they relate to both ethical tourism and larger environmental issues. If you’re reading this blog, chances are you would never partake in the activities described below, but it’s vital to educate tourists worldwide by spreading the word.

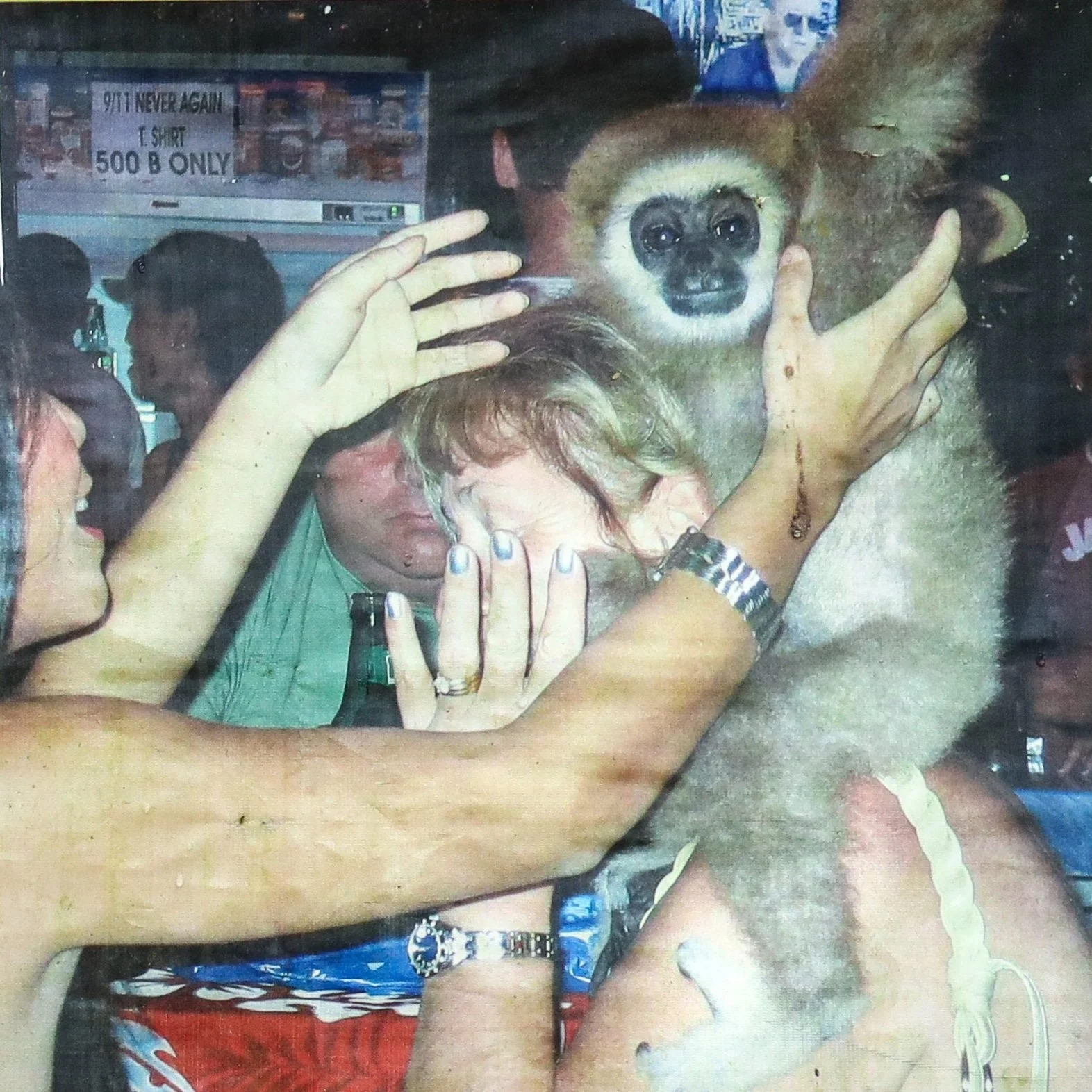

Image from the Gibbon Rehabilitation Project and the Wild Animal Rescue Foundation of Thailand (WARF)

First up: the tourism industry. Ever seen a post on Instagram or Facebook posing next to a tiger, riding an elephant, or holding a monkey? Chances are this is because of the workings of the illegal wildlife trade, and that the wild animal is heavily sedated or has been beaten and traumatized into obeying its human "owner." It has been illegal to hold a gibbon in captivity in Thailand since 1992, yet it’s still a huge problem due to tourist demand. Especially across the country's legendary clubbing scene, owners will approach tipsy tourists offering up a photo with their "pet" or showing off (for a charge) how their gibbon can drink whiskey and smoke a cigarette. Many tourists take them up on it. Unfortunately, as long as tourists want to take photos holding a monkey or see these unnatural spectacles, the problem will persist. Roch tells us that two simple solutions exist: don't be that tourist who takes photos of (or with) gibbons in captivity, and contact local authorities or animal rescue if you see it taking place.

Number two on the list: the illegal pet trade. Gibbons are sought after as pets all over the world, and as such, are poached to be sold on the black market. For both tourism and the illegal pet trade, the captive gibbon isn’t the only victim: to capture a baby gibbon — which poachers most often target — its parents are killed, since they will fight to their death to protect their offspring. Again, the solution here is simple: do not buy a gibbon, or products created from them.

Last and unfortunately not least: habitat loss. The number one driver of gibbons' endangered status is deforestation, with their natural habitat is being destroyed at the alarming rate of 32 acres per minute. Needless to say, deforestation is an immensely complicated issue that reaches far beyond one species, and that doesn’t have a simple solution associated with it.

Pretty dire stuff, I know. Especially considering gibbons are just one of the many species facing these prospects. But, here enters a source of hope: the work of the Gibbon Rehabilitation Project.

Founded in 1992, the project has rescued over 400 gibbons since its inception. The gibbons at the center have been rescued from a variety of destructive circumstances, each with their own story and trauma. Many of these animals require intensive medical care and years of rehabilitation before they can be returned to the wild, with some never being able to return due to the level of abuse they suffered.

Each gibbon has their own heartbreaking backstory of abuse before rescue

As we walk around the project site, our guide Roch tells us the story of many of the animals we are seeing: Bo was captured by poachers and kept as as a pet for years, before arriving at the sanctuary extremely malnourished with filed down teeth. Rumthai, kept inside a tiny birdcage, suffered from spine and arm deformation. Tam, orphaned at birth after poachers killed her parents, was later attacked by territorial male gibbons, resulting in the amputation of a hand and a foot.

Given the tragic and distinct backstories of each of the gibbons, the team at Gibbon Rehabilitation Project have gotten creative with their rehabilitation methods. Since there’s no guidebook to gibbon reintroduction, the team has experimented with different methods of rehabbing and reintroducing gibbons into the wild. Besides providing a new life for the reintroduced gibbons, the team's 30+ years of work in this field has also led to groundbreaking discoveries around the rehabilitation and release of apes worldwide.

Roch describes one of the reintroduction methods they found to be particularly successful: through matchmaking.

"After 7 years, sexual maturity, we try to pair two mature gibbons. If they love each other and have a baby, then we can try to release them into the wild," Roch says. "If they don’t love each other, then we try, try, try again."

Sounds simple enough, right? Wrong. Like with humans, love can be a fickle thing. "When you try to pair them, you cannot put them directly together. If you put them together, they’re gonna try to kill each other." Tough start to any relationship.

He continues, "So, we put the boy and girl in the different cage, and in the middle we have the tunnel, we call the 'tunnel of love.' If we see they might like each other, they’re making eye contact. If they don’t like each other, they’ll be banging like this on the gate," motioning with both his fists as if banging on an enclosure.

The gibbons at GRP live in spacious enclosures far from human contact to maximize the odds of successful wild reintroduction — they are even fed by a pulley system from meters away, and we took this photo from behind a camouflaged blind

"But if they like each other, then we open the first gate. Then when one of them goes inside the tunnel, and by the gate they will be hugging, this means they like each other. After that, it means we can open the last gate, and if they’re happy, then they’re hugging and kissing each other. Then it takes them a while to get to know each other. If they love each other, and after a while don’t have any problems, then we can move them together. If they don’t love each other, and they get a divorce, then we separate them and try again with a different one. Every step of the way we observe, observe, observe for information."

Beats any dating reality TV I've ever seen. I won't say I'm not angling for a long game National Geographic/The Bachelor crossover. Wild Love?

Anyway, back to the rehabilitation strategy: if a gibbon pair stays together for long enough and the team thinks they are ready, the pair will be moved into the wild. Given the relatively small size of the nearby rainforest, the team is able to monitor the reintroduced gibbons once they leave the center with the help of the surrounding communities.

While there is still an uphill battle (especially given pandemic-induced financial struggles), the project has achieved great success in its 3 decades of work: the wild gibbon population in Khao Phra Thaeo National Park has reached a point where they can repopulate on their own, and release efforts have expanded to a second site in the north of Thailand near Chiang Mai.

We end our visit to the Gibbon Rehabilitation Project how any financially savvy operator does: with the option to make a donation or purchase an item from the project's small store to support their work. I browse the selection of gibbon-supporting projects and decide to purchase a yellow tote bag emblazoned with the project's logo on it — an affordable and practical item I can use to spread the word about this special project.

And here, dear reader, is where our story opened. While it was obviously indicated on the packaging, I had not just bought a tote bag — I had bought a tote bag with a certificate of adoption, signifying that I would fund the food, supplements, and care needed to maintain one of the project's gibbon for 3 months. What I thought was a $3 tote bag was actually a donation of about triple my daily (economy backpacker) budget.

As Roch filled out my adoption paperwork, I considered if I should try to explain the situation to him, that I had misunderstood, and make a smaller donation — then realized I didn't want to. After he finished filling out my name, he asked me to go look at the wall and select the gibbon I would be sponsoring.

From a wall of gibbons, my eyes landed on a photo of Emily, a white-handed gibbon with a fluffy, caramel colored coat and big eyes. The bio under her photo read:

Born at GRP to Nuan and Max in 2011, sadly after birth her mother showed no ability to look after her so had to be taken away to be hand-raised. Bruised and with damage to one of her fingers, Emily was an incredibly shy and quiet introvert as a baby. She would often curl up and suck her thumb for comfort. Luckily she was soon able to share a cage with her 1-year older sister Maesa, who also was rejected by their mother. Eventually the sisters, along with their friend Arya, progressed in their rehabilitation process so that they were able to be moved to Phi Phi. Being egged on by bossy Arya, it seems Emily's confidence has grown and grown. She's much less dependent on people than she used to be, which is exactly what we like to see. In 2019, Emily paired up with Willy, they are so bonded together and we hope they’ll have a baby soon.

I let our guide know I'd like to adopt Emily and smile, knowing there are much worse mistakes to make. And to you, dear Emily: I hope you have the best 3 months of care of your life so far — and that it only gets better from there.